Why burn peats?

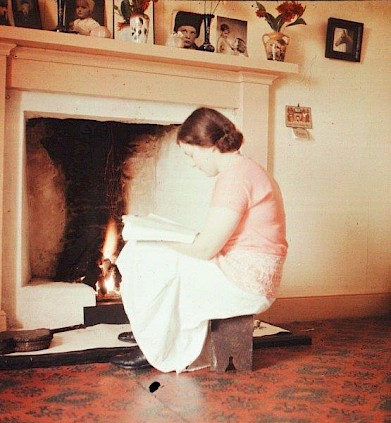

Local fuel was essential to life. When people settled on the fringes of the British Isles, their livestock destroyed native trees there. However, peat provided abundant fuel; it covers most of Shetland and the Hebrides, but there’s less in Orkney. Islanders used it intensively over millennia, on the sustainable scale that subsistence entailed. On the moorland, people burnt heather to encourage grazings, harvested plants for ropemaking, and prepared fodder. The greatest work was the manufacture of peats for fuel.

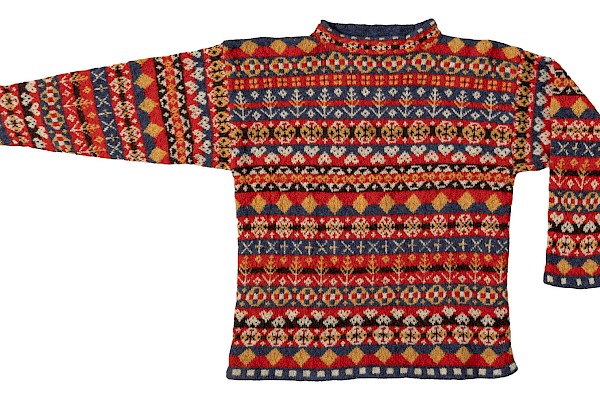

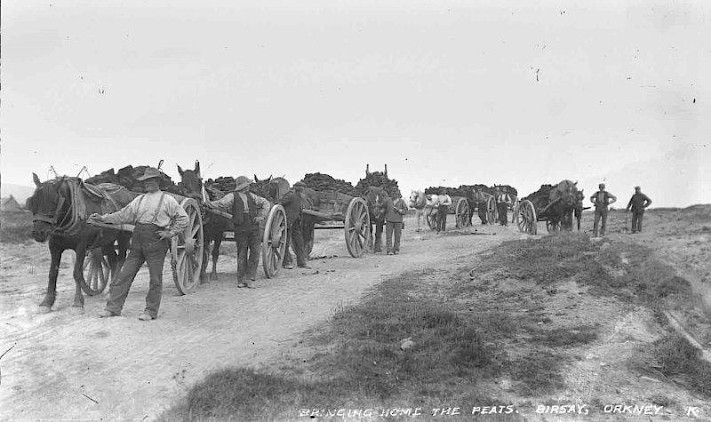

People are drawn to the spectacle of peat cutting, but that was only the beginning of the process. Work was intensive, but had a convivial nature, with everyone working together turning and heaping them, then getting them home. Depending on geography, the community might use boats or packhorses, or individual families could have a sled or cart. Later, the wheelbarrow and tractor-trailer took their place. The last stage was to stack them, to keep the rain off.

Peats were vital for more than heating and cooking. Peat fires dried grain, sustained fishermen afloat, made building lime, forged iron. Peat dust was valued, as was its ash: everything had a use. There was much work involved in winning peat, but it was guaranteed to be there. Technically non-renewable in modern parlance, the supply would have lasted thousands more years had our way of life never changed.

The islanders’ use of this free fuel declined long before modern concerns about carbon reduction. Firstly, imported fuel came from the 19th century. Coal fuelled businesses and homes in towns, giving better heat than peats. It heated schools, industries had equipment driven by steam, and fishing boats started using coal. Secondly, islanders’ living standards improved through the 20th century: by the 1970s even rural folk abandoned peats in favour of oil central heating, and councils built houses with electrical heating. This was possible because more people had no connection to the land, and families had money to pay for services. We enjoyed easier ways to cook, and electricity or oil fuel was cleaner.

There was still a demand in the 1980s-90s for peats. Mechanisation meant less human input, and more working by heavy equipment on a large scale. People had money. Thus, commercial peat cutting came, particularly in the Hebrides and Shetland. Purists declared the product wasn’t as good as “real peats”, and the machinery made a mess of the land. But people bought them.

Peat is formed by decaying moss. This removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, regulating the climate by storing carbon within the moor. When this is burned, it’s even more damaging than coal. Commercial exploitation (i.e. not traditional subsistence) for compost or fuel has spoiled peat’s reputation in the eyes of many outwith the islands.

But, consider the full picture - for example, builders’ lime. Islanders made this with local stone and peats, but masons today use lime imported from France, made on a huge scale far away, and brought here on a road/ship infrastructure that’s more destructive to the planet than indigenous peat burning was. Peatland is now at the mercy of forces that have the power to destroy it more effectively than millennia of islanders ever could. Overgrazing by sheep farming has broken ground surfaces, causing erosion, and bog drainage has had similar effects. Thousands of tons of moor are being displaced for roads, concrete, and building sites. Peat’s story isn’t simply cut and dried.

Find out more: Follow the links to find out about the Between Islands project, Shetland’s new online exhibition, ‘Fair Game.