Who was Janet Courtney?

It’s that time in August now, the new school term is near, new experiences, people, and challenges. For many Shetland children, a new term meant living in a new place, residential education in Lerwick, some spending as much as a whole term there. For rural boys from 1947 onwards that meant living in the Janet Courtney Hostel, an imposing edifice at Twageos, now awaiting redevelopment. But who was Janet Courtney?

Image: Mrs Janet Elizabeth Courtney OBE © Imperial War Museum

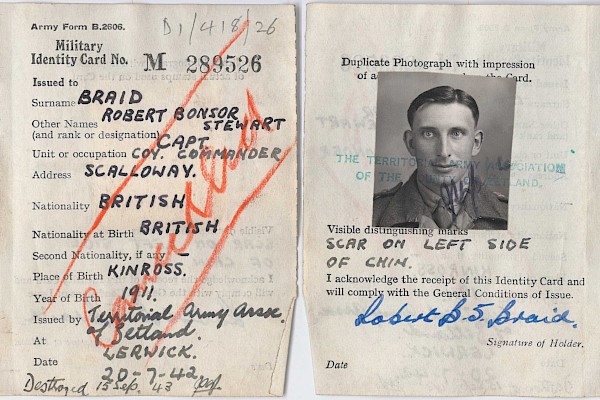

The hostel financiers, Carnegie United Kingdom Trust, named the building after her, but there were few other details. Was she somehow connected with Shetland and possibly Jannie Courtney, not Janet Courtney? The imagination conjured up a fleeting image of an older woman in a long fur-collared coat.

Image 1: Janet Courtney Hostel under construction, 1939

Image 2: Janet Courtney hostel pictured in the background, 1961

Janet Elizabeth Courtney wrote a memoir Recollected in Tranquility in 1930, describing a life far away from that lived in the hostel. She was born in 1865 in Barton on Humber, Lincolnshire, to an Anglican clergyman the Revd. George Hogarth and his wife Jane Uppleby. George came from Makerstoun, Roxburghshire. The family had no Shetland connections at all. There were fourteen Hogarth children, nine living to adulthood. The family valued books and learning for girls Victorian style, governesses included. They spent afternoons sewing, “and reading aloud in turns.” Janet loved reading, saying of the book John Inglesant, a novel of ideas – “for six summer months in 1881 I lived in the book – I forgot everything else.”

After a spell in Grantham Ladies College, Janet went to Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford University, in 1885. Her father allowed it, after doubts. It was the first time she had a room of her own. The college gave her independence, freedom, stimulating companionship, and some moments of daring. Women students were chaperoned to lectures and tutorials. One day the chaperone didn’t turn up, so she entered the lecture by herself. Nothing happened.

In 1888 she got a first-class honours philosophy degree without graduating, Oxford didn’t allow that for women. There wasn’t a place there for clever young woman like her. She taught part-time at Cheltenham Ladies College, then worked as a clerk for the Royal Commission on Labour in 1892. In 1894 she was a superintendent of women clerks at the Bank of England, which involved, among other things, laying out “banknotes in patterns like patience cards.” She wrote clerical work “was a soul-destroying avocation, from which any woman, let alone a woman of higher education, might well pray to be delivered.”

Mental stimulation was writing – articles and reviews – and work on the influential literary magazine The Fortnightly Review for her former tutor William Leonard Courtney. Widowed in 1907, he married her in 1911, and she became

Mrs Janet Courtney. Before that, she’d been chief librarian for the Times Book Club in 1906. Better than the Bank, or clerical work. The “Club” was a free lending library for Times subscribers, a perk to increase subscription and advertising. Good job or no, some things she wouldn’t put up with, and an attempt to introduce a censorship system caused her to leave.

In 1910 she was working on the eleventh edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, a ground-breaking part of encyclopedia history, and again she was in charge of a large group of women employees, sub-editors, and crucially, indexers. She got indexing process under control – “The clerks boiled kettles all day long and wasted even more time than in government offices.” Order prevailed in the end. The Britannica held a dinner at the Savoy for the limited number of women contributors in December 1910. Hugh Chisholm, the editor, toasted the “work of the women.” Janet replied, noting women were entering fields where they were previously excluded, and in indexing women had “fulfilled our feminine function of keeping things straight.”

The speech sounds feminist, but perhaps the term “feminine function” indicates something slightly different. In 1908 she was on the executive committee of the National Women’s Anti-Suffrage League, along with her friend Gertrude Bell, the Middle East expert. Surprising now, but they seem to have feared that the Pankhurst militancy might be counter-productive. The anti-suffragists gained little traction, and Janet Courtney changed her mind after marriage on realising how few rights she had then. Even so, in 1933 she wrote that the vote “was a double-edged weapon of limited usefulness,” and involved women in “strife of parties.”

Leaving the Britannica in World War One, she worked for the Ministry of Munitions as a Welfare Advisor. She gained an OBE in 1917, having investigated the work and conditions of large numbers of women typists, and re-organised it to be more efficient. The work of an organiser who wished to keep things straight.

After the war she started writing books in earnest, starting with Pillars of Empire, with her husband in 1918, then Freethinkers of the nineteenth century in 1920. Between 1920 and 1922 she worked on the twelfth Britannica, and toured the U.S.A. with Hugh Chisholm to promote it. Her husband died in 1928 and she was awarded a civil list pension of eighty pounds a year, and took over the running of the Fortnightly Review in his place for some months.

She’d become a trustee of the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust in 1913, staying for 32 years, retiring in 1946. It was a good fit for her, the trust devoting resources to libraries and educational facilities. At the opening of library in Slough in 1924 she made the point that the trust could finance books, but keeping the library going was up to the ratepayers. Later, in 1939, she was a member of committee investigating what the trust could do for British music in 1939.

The Carnegie Trust had financed accommodation for rural pupils in Scottish islands between the wars, and finally the boys’ hostel in Lerwick. Meant to open in 1940, the war ensured delay until 1947. The trust commemorated their long-serving member, naming it the Janet Courtney Hostel. She was nearly 82 then (she died in 1954) and felt the journey north wasn’t for her. Ernest Salter Davies, the Carnegie chair, read out a letter from her, saying her thoughts would be with the opening of the hostel “which you have done me the honour to christen in my name.”

Janet Courtney is a figure in women’s history, her roles in the Britannica and the Bank of England mean she gets referenced. Writings about Lady Margaret Hall and the prominent women she knew are quoted, along with her observations about lives and conditions of female office workers. The Janet Courtney building, apart from a gravestone, is the only visible memorial of her name.

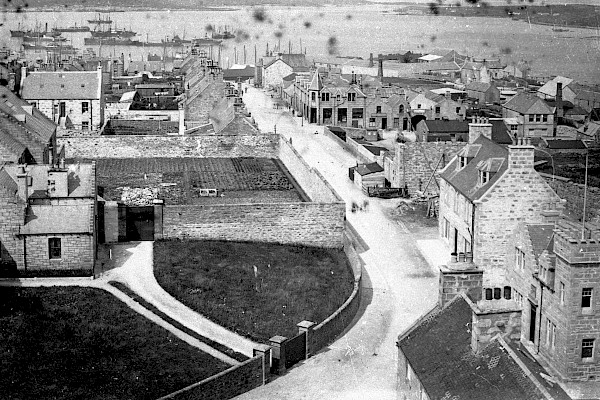

Janet Courtney Hostel, Lerwick 1985. First occupied after World War II by boys attending Anderson High School. Later extended on left, Anderson High School buildings on the right.