The Story of the Black Book

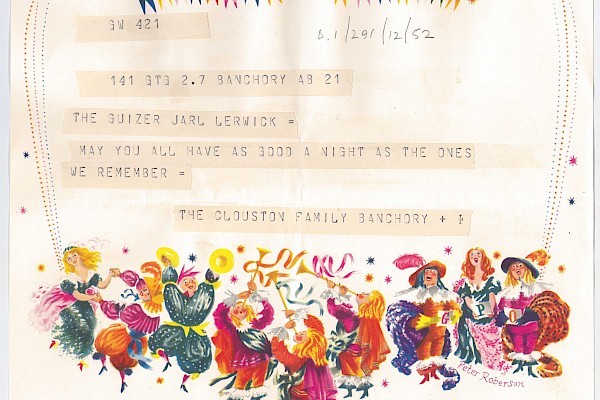

This week’s 'Shetland Spooky Stories' event was a big hit. One tale that especially gripped our audience was 'The Black Book', written by archives assistant, Mark Smith. The story was inspired by a recording in the archives of a man from Cullivoe who spoke about the mysterious Book of Black Arts. Read Mark's full story here...

I first heard about the Book of Black Arts from an old Cullivoe man. He’s dead now. He was a storyteller, one of many in his family, and, as a way of keeping their stories alive, a recording was made of him. It is this recording I have to thank, if thank is the right word, for the story I’m about to tell.

I first heard about the Book of Black Arts from an old Cullivoe man. He’s dead now. He was a storyteller, one of many in his family, and, as a way of keeping their stories alive, a recording was made of him. It is this recording I have to thank, if thank is the right word, for the story I’m about to tell.

When I heard about the Book, part of my work was to make transcriptions of reel-to-reel tapes in the archives. There are hundreds of them. I can still remember the smell of those tapes – musty when a lid was lifted, then a warm, sharp chemical smell would fill the room as the tape ran through the machine. There was always the fear a tape would break. They hadn’t been played in so long. One moment of accidental tension and the voice would be gone forever.

Here, as far as I remember, is what he said about the Book:

For example, I do know that in North Yell there was a

Book of Black Arts in circulation.

He didn’t know how the Book had come to Cullivoe, but in his grandfather’s, or maybe great-grandfather’s, time, it had passed through the village, from hand to hand. It was filled with what he called ‘mystical rites and spells’, it had white writing on black pages, and it could not be given away. Once the Book came into your possession, the only way to escape its dark influence was to sell it for less than you paid. This could only go on for so long. Sooner or later, as the price dropped to nothing, somebody would be stuck with the Book. And what would they have to sell then? What would the cost be, in the end?

I reached the end of his story and stopped the tape. The reels of the machine observed me like two enormous eyes.

As I worked at my transcriptions, I remembered a story by the Argentinian writer Jorge Louis Borges, where an Orcadian appears in Buenos Aires with a similar mysterious book.

The folk traditions of Shetland and Orkney share several themes, but the Book of Black Arts is mentioned more in Orkney than it is here. Borges, in faraway Buenos Aires, knew what he was talking about. The Argentinian man who acquires the Book in his version escapes by placing it in the National Library. But should some casual browser withdraw the Book, they’d be one of its people too.

I wrote a short article on the Book of Black Arts for the Shetland Times. People seem to enjoy colourful little folk stories about quaint local traditions, and, even though the article contained no great insight, I couldn’t help feeling pleased with the nice comments that started to appear below the online version. But, hidden in in a lengthy, rambling comment by somebody calling themselves ‘Gilmartin’, I found the words that appear on the first page of the Book of Black Arts:

Cursed is he that pursueth me.

It took a bit of reconstruction, but the phrase was there. Without a doubt. A payload of six words sent my way, subtly smuggled inside the bulk cargo of a BTL contribution. Gilmartin clearly knew the story of the Book and was having some fun at my expense.

Before the story was removed from the Shetland Times site, Gilmartin appeared another three times, always with sly references to the Book’s story: mentions of people who once held the Book; a sneaky anagram of the name of an Orcadian minister who buried the Book in his garden. Gilmartin was clever and I wanted to ask what he knew. I got his email address from the Times and sent him a message.

An email came back right away. I opened it but it said nothing. Not a single word. Nothing but a black mass filling the message window. Another Gilmartin joke, I assumed: the E-Book of Black Arts. I closed the laptop. Maybe he would write back soon.

Then the words started to disappear.

It was barely noticeable at first. I would open a document I’d been working on and, when I tried to pick up where I’d left off, it didn’t quite match what I’d written the day before. A phrase was suddenly incomplete. A plural would be sliced to the singular. Verbs were yanked from the middle of sentences, leaving subject and object to stare out in confusion as they waited to be given something to do. Holes appeared in paragraphs I thought I’d refined until they were as good as I could make them.

I assumed there was something wrong with the laptop. I did what checks I could and, when that made no difference, I took it to the IT department. They found nothing wrong. It must be something you’re doing, they implied. Perhaps, they hinted, I wasn’t as good a writer as I liked to imagine. I picked up the laptop and swept out of the room.

From then on, I took great care over everything I wrote. But, even so, I couldn’t deny what was happening. The words were disappearing. Words I had typed, sometimes more than once, simply weren’t there when I went back to the document that once held them. And it was happening faster than before. I couldn’t keep up. I would put the words on the page but couldn’t make them stay.

Then, months later, Gilmartin wrote back:

Dear Dr Smith,

Are you enjoying our little game? We certainly are.

Taking your magic box to the IT department was

splendid fun. They really got under your skin, didn’t

they, with their idea that a shoddy workman always

blames his tools. But all these pixels and bytes you

people are so fond of are so easily lost. Don’t you agree?

It’s not like the old days when words were written on

proper vellum, or carefully copied onto good paper in

lovely dark ink. But we found our ways back then too,

as you’ll see when you follow the directions we are about

to send.

Yours, ever, etc.

G.

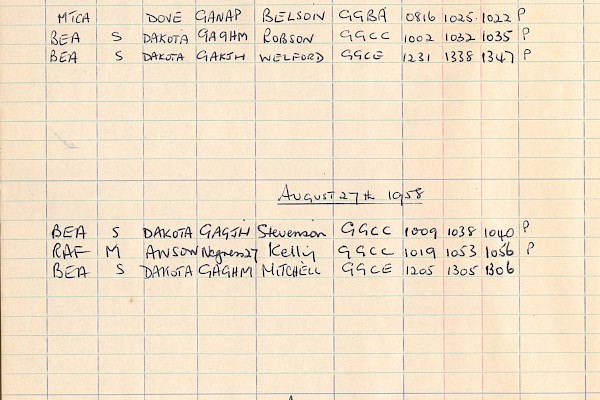

What followed was an email with reference numbers to documents here in the archives. I took my laptop and went upstairs to the room where the documents are kept.

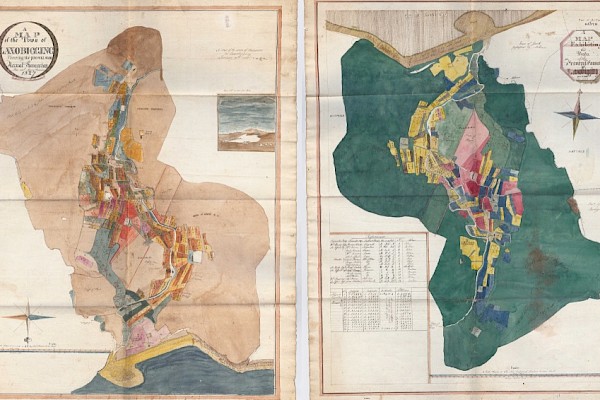

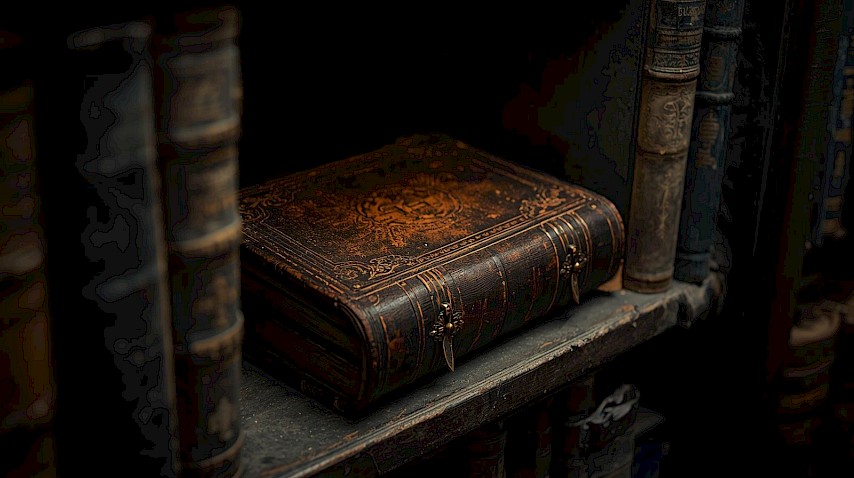

I switched on the lights and went inside. There is a long alleyway through the centre of the large room, with dozens of shelves running away on either side. Halfway along each of these shelves, each of which holds dozens of boxes filled with hundreds of documents, is an opening which lets you through to the next set of shelves. I looked at the first number and found the place where the document would be.

It was a rolled piece of parchment that hadn’t been looked at in years. I untied the piece of ribbon that held it closed.

Because of the dim light and the old handwriting, the document was hard to read. I would take it to my desk and make a transcription, I thought, but, as I scanned the text, I could see, in the crowded lines, that there were obvious gaps. The flow of ancient words, with their ligatures and lobes and serifs, would be stopped dead by a hole in the middle of a sentence. Sometimes there are blanks in an old document, a place for a name or a date to be added, for example, but this was different. As had happened with my laptop, the words had been made to disappear.

Feeling my heart quicken, I concentrated on rolling the document and knotting the ribbon around its middle. The words were gone. That was impossible. But it was true nonetheless. I reshelved the document and moved to the next reference Gilmartin had given me. It was a diary kept by a sailor in the 1850s. The same thing had happened. His words had been taken away. They simply weren’t where they should have been. I put the diary back, looked at my laptop for the next document, and went to see what else Gilmartin had done.

I don’t know how many hours I spent walking past rows of shelving in the gloom, stopping occasionally to look inside another of the boxes Gilmartin had sent me to. I understood how he might infiltrate my computer and corrupt my files, but how had he done this? Nobody has access to this room but me.

I decided to retrace my steps. Back then, I still felt there had to be an answer somewhere. I worked backwards through Gilmartin’s list, carefully reading each document as I went. There were blanks and cuts on every page. Words had been removed from documents I knew well. Spaces opened in texts that had been written hundreds of years ago. I kept going, trying to remain methodical. I kept moving through the maze of letters and diaries and deeds and accounts that Gilmartin had laid out for me. I walked past miles of shelves. I don’t know how long it took. There are no windows in this room and you lose track of time.

Eventually I reached the sailor’s diary. Sitting on the floor, I opened the little book. There was nothing there. All the words were gone. I turned the pages. Whatever the sailor had written had been rubbed away to nothing. It was gone. It was all gone.

I slumped against the wall and closed my eyes. Perhaps I fell asleep. I’m not sure. But the next thing I remember is the soft chime my laptop makes when an email is received. I opened the lid and the screen lit up. The email was from Gilmartin:

Dear Dr Smith,

You will, by now, have reached the end of the jolly

itinerary we planned for you. Don’t you enjoy a

nice ramble through the historical highways and

byways? You will also, no doubt, be asking yourself

how we accomplished our little vanishing trick. Well,

my good doctor S, it’s really not as complicated as you

might imagine. We have, after all, had plenty of time

to practice these things. But, my dear man, you should

not worry yourself unduly. The words are quite safe.

We’re not, after all, in the business of mindless vandalism.

History can never be erased completely; it’s simply a

case of who gets to tell the tale. If you look back at the

first email I sent you all those months ago, you’ll find

your missing words.

With the warmest regards, etc., your friend, G.

I found Gilmartin’s email and opened it. The black window appeared but, as I stared at the screen, I began to see, as if deep inside the thin wafer of the laptop’s lid, words starting to emerge. Words floating to the surface of the screen. White words fixing themselves to the blackness of Gilmartin’s message. Old Scots and Norse words. Legal words from court documents. Words from diaries and letters. Words I had read in old documents. Words I had written myself. It was all here. All the words he had taken. Words filling every part of my screen.

I scroll and scroll but I can never find the end. Gilmartin has taken it all. His black message consumes everything, sucks everything in like some ravenous digital mouth. Even as I sit here, he is probably adding to his horde, words and syllables and punctuation marks funnelling into his unfathomable black space. The story of me. The stories in these documents. The story of this place. Every story that I am even a bit-part character in, the black square wants them all. Even these shelves and these walls and this floor I’m sitting on. It’s all disappearing. All moving towards silence. Things don’t exist if they can’t be spoken about and it’s all being pulled into this single black square.

Sometimes I walk. Then I sit down and add a sentence or two to this account. It is holding together so far. The words are staying where I put them. Sometimes I tell myself that he has taken everything he’s going to take. But then I look inside another box and find empty page after empty page. Gilmartin won’t let a single letter escape. He is toying with me. These words, the ones you are hearing now, will be sucked in like all the rest. But still I type. One word after another. Telling this story in the hope that it will last long enough for someone to know what has happened to me. But I know it’s futile. I know, in the end, that my story will disappear, just like all the rest. Then, when he wants it to, it will drift to the surface of this screen, a collection of white words caught in the frame of his deep black square.

Copyright: Mark Smith

The original conversation with Cullivoe man Tom Tulloch, recorded during a 1980 interview by Jonathan Wills for Radio Shetland, is available in the museum archives.