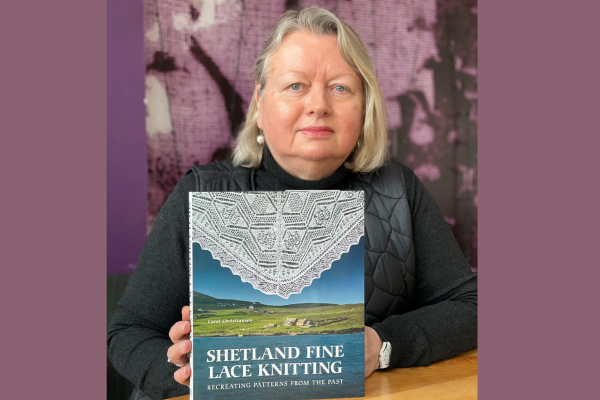

Face Veils: a Victorian Fashion Accessory for the New Norm?

In the past few years there has been discussion, and at times heated debate, about whether women should be allowed to cover their heads and faces in public. The COVID-19 pandemic has placed this issue in a fresh new light. Face masks are now manufactured at a rate never seen before, authorities encourage at-home sewing of cloth masks, while governments consider whether face-coverings should be made mandatory in public. The burqa-wearing women who Boris Johnson compared to letter boxes in 2018 may be having the last laugh as we all try to safeguard ourselves from a viral pandemic.

A Shetland bride c1890s, wearing a white net face veil decorated with beads

Women, and sometimes children and men, have been covering their heads and faces in public since ancient times. Not so very long ago many women in western cultures wouldn’t dream of leaving the house without wearing a hat or scarf. My grandmother, born in the United States in 1891 to poor but respectable immigrants from Luxembourg and Sweden, always put on a hat before she went anywhere, even as late as the 1960s. Hats are an essential accessory for weddings and christenings in the UK, and head-coverings are still worn to religious services in many faiths. Brides cover their faces with veils until the marriage vows are completed and veils are worn by girls at their confirmation. Who can forget the images of Jackie Kennedy and Coretta Scott King at the funerals of their respective husbands, wearing full head-covering, shoulder-length black veils, or the three queens – Elizabeth II, Elizabeth the Queen Mother, and Queen Mary wearing the same at the funeral of George VI? Covering one’s head remains a gesture of piety, respect, chastity, and sorrow even in the increasingly non-religious West. Covering one’s face is now a matter of personal protection against an as-yet unchecked contagion.

If face-coverings are destined to be the new norm, we may want to take some tips from the Victorians and Edwardians. When it comes to covering the body in fashionable accessories, they were unrivalled. Hats were essential and veils, as an accessory to hats, were a regular feature. A face veil signalled social status and expressed femininity, reservedness, even coquettishness. It also served as a necessary accessory during periods of mourning, which were lengthy and could be frequent. On the practical side, a veil helped to protect a woman’s face from sun, rain and pollutants, as well as airborne dirt, dust, and exhalations from people and animals.

Shetland woman wearing a ruff band, to which a black veil hangs at back, c1860 (ART 2002.161)

Veils were an accessory to a head-covering, whether bonnet, hat, band, ruff, or decorative fabric, and attached to it. Some veils were designed to cover all or part of the face, or gathered at the back of a head-covering to fall down the back, sometimes to the waist. Hat styles changed significantly between the 1840s and the First World War, ranging from modest, face-framing bonnets to expansive hats piled high with flowers, ribbons, feathers, and even stuffed birds. The size and styles of veils changed accordingly. They were rectangular or half-moon shaped, which covered the face to the bridge of the nose. With the popularity of the open-carriage automobile in the Edwardian period, a new accessory, the motoring veil, became necessary to safeguard enormous hats from blowing away under speed.

A home-made type of motoring veil to secure a very large hat, c1890s

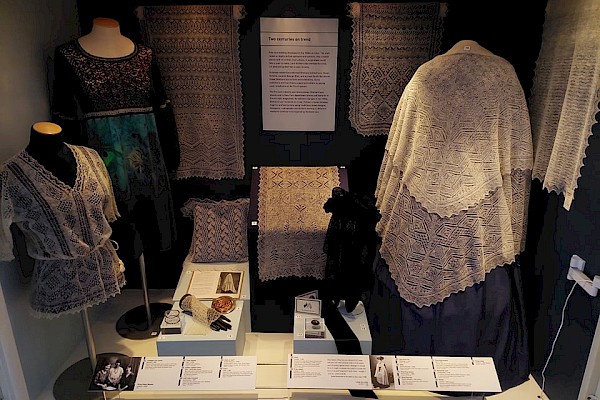

Like many dress accessories in the Victorian period, veils were rendered in the Shetland lace design tradition as early as the 1840s. They formed an important product in the Shetland lace industry for the rest of the century. Indeed, some women identified themselves exclusively as veil knitters in 19th century census returns and the Truck Commission interviewed veil knitters in 1872. Like shawls, veils were made almost exclusively for export.

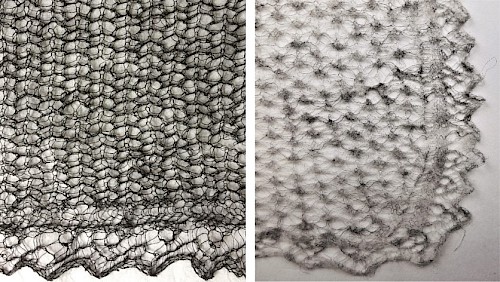

Shetland knitters made veils from mohair and machine-made wool imported from the British mainland, but they could trade veils at a higher rate with the merchant if they used Shetland wool, which in this period was all hand-spun. Some knitters spun it themselves, bought yarn from a local hand-spinner, or purchased it from the merchant. Merchants complained that hand-spun Shetland wool supplied to knitters looked good when handed out but came back with linear colour variations, forcing them to send the finished veil to the Scottish mainland to be dyed (Commission, 1872: entry 3100). This was due to colour variations in Shetland fleeces and could not be completely rectified through blending with handcards. But merchants also knew that even the blackest Shetland fleece is in reality a very dark brown, so for a true black the veil must be dyed, yet they continued charging the cost of veil dyeing to the knitter (Commission, 1872: entry 3318). All of the black veils in Shetland Museum’s collection are dyed.

Dyed black veils were worn for full mourning (generally one year) and replaced by natural grey veils for half-mourning (six months). TEX 2004.343 and TEX 8936.

The strict formal codes of mourning in the 19th and early 20th centuries meant that black veils were a necessary accessory. Lighter coloured veils, in grey for example, were worn during the period of half-mourning. An early 1920s price list for Shetland knitwear from Miss E. B. Harcus, Scalloway, lists (semi-) circular and square (i.e., rectangular) veils in natural white, grey, and dyed black (TEX 1994.658).

Veil design

Shetland Museum has rectangular and semi-circular face veils, all for attaching to head-coverings. They have several key similarities. One long edge has knitted-in holes to attach the veil to a head-covering. A cord or ribbon was threaded through the holes and tied around the base of a hat crown and covered with a wide ribbon or other decoration, or used to sew the veil to another type of head-covering.

Detail of semi-circular black face veil with very small eyelet holes at top edge. TEX 2004.348.

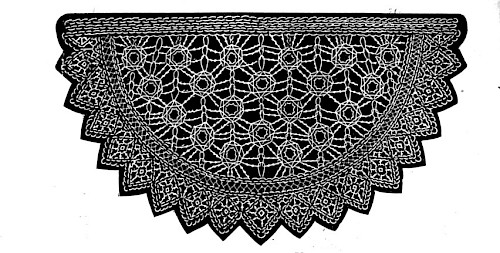

Although the drawing is nowhere near to scale, the design for this 1867 knitting pattern for a Round Shetland Veil is essentially the same as the veil above (Riego de la Branchardiere).

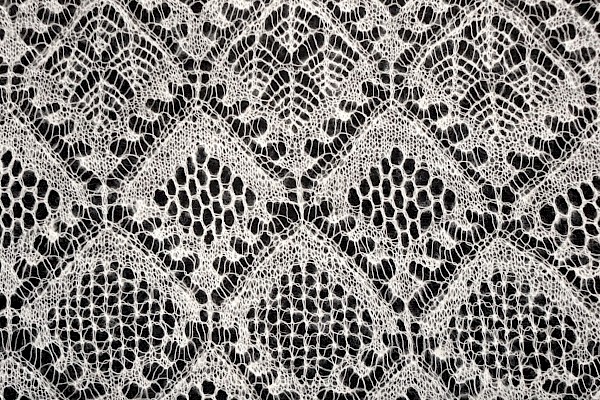

The main centre pattern for all face veils is a single, simple, openwork motif to allow the wearer to see through the fabric. Shetland knitters used a limited range of patterns such as bead, roach or spider for veil centres. A simple lace edge was used around all edges except the long eyelet edge. Veils in the collection range in size from 30 x 77 cm to 28 x 122 cm. As lace pieces they are a relatively simple construction and veil knitters could make up to three per week (Commission, 1872: entry 2085).

Face veils for infants

Shetland Museum has two face veils made for infants and we are aware of two others. The practice of veiling infants is known from mainland Britain; in Shetland veils are recorded being used to cover infant’s faces at christenings and during its first public outing. Veils were attached to the infant’s cap, which could be large, so that the veil spanned the face rather than rested on it.

Semi-circular veil for a baby boy, born in Lerwick in 1886, 28 x 57cm (TEX 1994.370).

The purpose of infant veils also may have been to protect the child’s face from sun and cold weather, while still allowing the carer to see the child in the pram. Creating a barrier from people carrying disease may have also been a factor, although the mechanisms behind the spread of contagious diseases were not always well understood by the general public. However, the age group with the highest proportion of deaths in Scotland in the mid-19th century were children under age five (Knox :3). Diphtheria, scarlet fever, measles, whooping cough, tuberculosis and influenza were common diseases. By 1898 infant mortality in Scotland was 129 deaths per 1000 live births, or one death for every eight surviving children.

Infant face veil 48 x 30cm (TEX 2004.368). The lower border has a 4-stitch cable of three twists. Twisted stitches are unusual in the Shetland lace stitch repertoire but not unknown.

Infant face veils are smaller than those made for women and tinier pattern designs were chosen or knitted at a smaller gauge. The child did not require to see through it, but the fabric needed to be open enough to allow the child to breathe comfortably. They are just as decorative, if not more so, than face veils made for women.

Is it time to resurrect the knitted face veil? While Shetland lace veil designs would not guard against respiratory disease, the patterns would provide a decorative surface to a mask made to recommended guidelines.

References

Commission appointed to inquire into the truck system (Shetland). 1872. Second Report. Edinburgh: Murray & Gibb.

Knox, W. W. ‘Health in Scotland 1840-1940’ (Summary). A History of the Scottish People. https://www.scran.ac.uk/scotland/pdf/SP2_3Health.pdf, accessed 30 April 2020.

Riego de la Branchardiere, Mlle. 1867. ‘Shetland Round Veil’, The Abergeldie Winter Book, London: Simpkin, Marshall, & Co., p.24-25.

We hope you have enjoyed this blog. We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.

We hope you have enjoyed this blog. We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.