The ‘Churchill’ pattern

From Selbu to Scalloway, via Whalsay and Lerwick: tracing the so-called ‘Churchill’ pattern

Occasionally a single knitting motif sparks the imagination of many people – brought to life by one creative knitter and reproduced time and again, it soon becomes a star in its own right. As it travels through time and space, its origin may become forgotten or obscured and many lands and many hands claim its birth-right. But these assertions merely attest to its timelessness as a pattern, its popularity in different cultures, and its continued interest to handknitters.

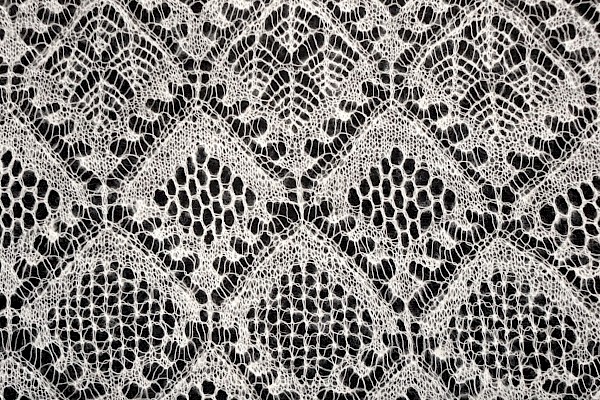

One such pattern is a large, square but intricate motif of medallions and arrows. It originated in Norway but has been knit in Shetland for many years. It appears early in one island community but latterly has been referred to as the ‘Churchill’ pattern, after it was used in a pullover knit for Sir Winston himself. It’s many variations over more than a century, and the ‘Shetlandisation’ of this classic Norwegian motif, confirm its popularity among Shetland knitters.

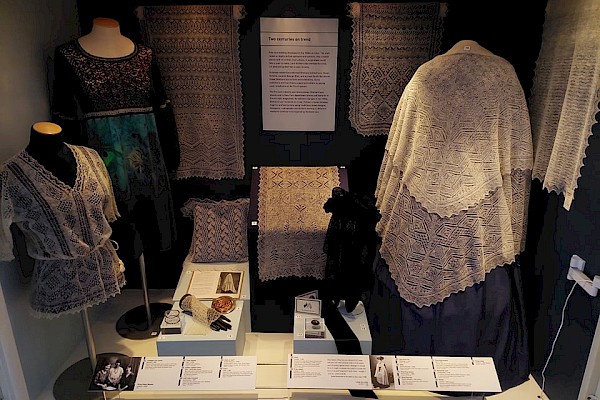

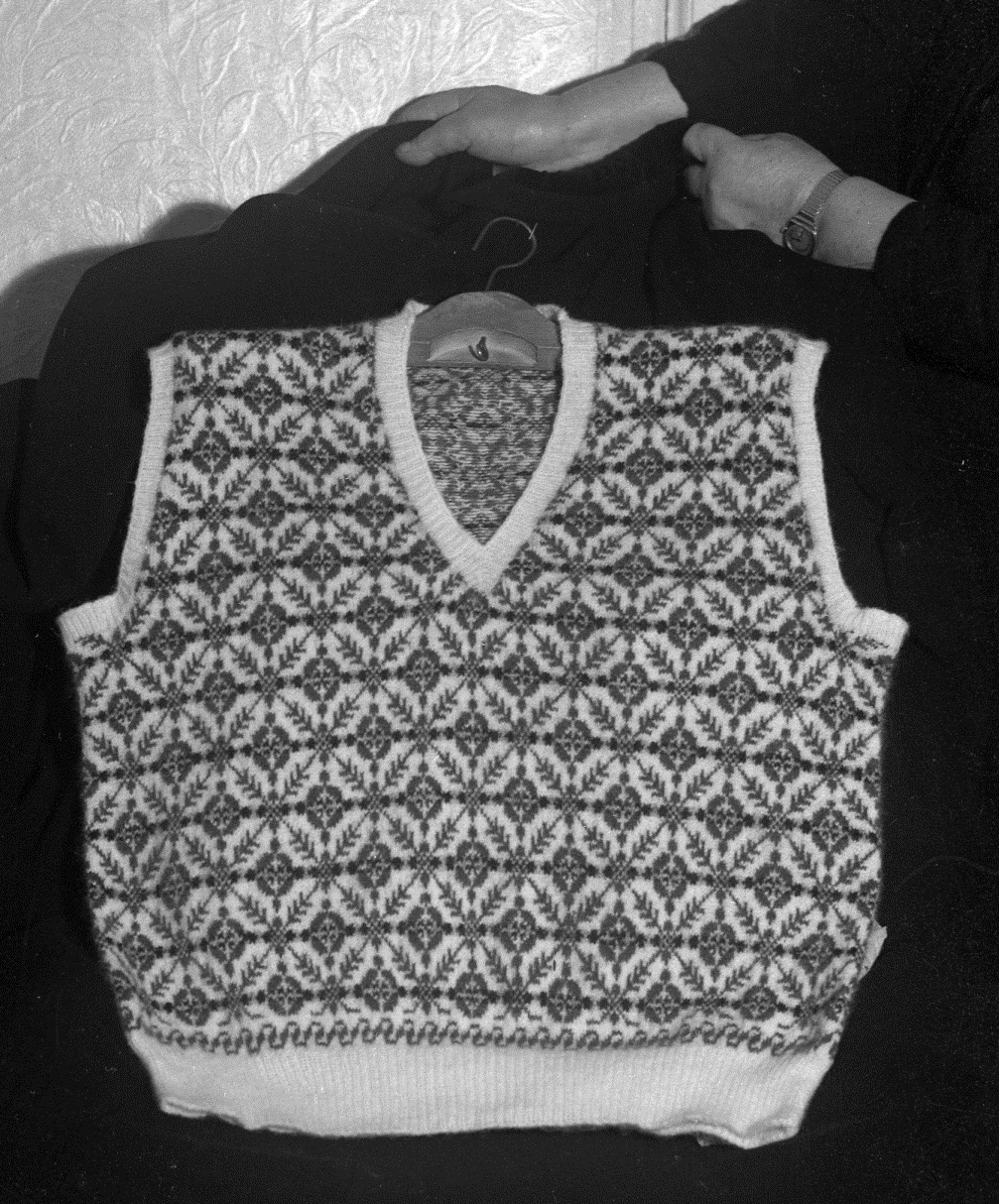

Shetland's knitters made the black and white Norwegian pattern their own by applying their trademark colourwork. Shetland Museum Textiles Collection.

Norwegian origins

The community of Selbu, Norway, located in the middle of the country just north of Trondheim, is where a number of two-colour knitting patterns originated. In particular, the Selbu star or flower motif is part of the local repertoire, yet has become the logo of a number of Norwegian wool craft enterprises, as well as a symbol of Norwegian knitwear in general. The Selbu style of knitting, using two colours (usually black and white) to make intricate designs, is attributed to a local woman, Marit Emstad in the late 19th century. The patterns were used in jumpers, but more commonly in stockings and mittens. The popularity of the patterns was so widespread, and the Selbu knitters so prolific, that the knitwear was sold, traded and exported.

It is not known when Selbu style patterns first appeared in Shetland. Shetland knitters were careful to remain true to their own traditional patterns for knitwear they exported. The fair isle ‘brand’ was successful and it would have been risky to adulterate it or confuse the dedicated customer base by introducing Norwegian patterns. But knitwear made for themselves or their families was a different matter and here Shetland’s knitters were less prescriptive and more apt to experiment with styles and patterns that caught their fancy.

The Whalsay connection

Irvine and Maggie Shearer (née) Hutchison) wearing versions in opposite colourways, c1930

The island of Whalsay lies on the eastern side of mainland Shetland, the most easterly island except the Skerries archipelago, to which it is culturally linked. Whalsay has its own strong identity as a community based on fishing and all that that signifies: hard work, a sharp intelligence, bravery, risk. Its inhabitants speak a different dialect, and the island has a reputation for very colourful knitting.

Whalsay Heritage Centre recently mounted a large, outstanding exhibition of island knitting from the 20th century. One photograph shows friends Babbie Jean Poleson (née Irvine) and Maggie Shearer (née Hutchison) wearing pullovers in the Selbu arrow and medallion pattern. Both women married in 1935 but the photograph was probably taken earlier, very late 1920s or about 1930. The jumpers are tunic-style, one with V-neck, the other a square neck. The ribs are ‘loop-about’ style using two alternating colours and the lower basques and wrists have different wavy designs dividing the ribs horizontally. The jumpers are knit in opposite colourways, light against dark and vice versa. Seeing them next to each other, it is easy to see how both colourways bring out different aspects of the delicate design.

This pattern has another link to Whalsay from the same period. Emma Gray from South Shields married Lowrie Irvine from Whalsay in 1931. She began to knit fair isle soon after her marriage and, as many knitters did, kept a graph book where she recorded patterns. In it she jotted a version of the Selbu pattern, which she titled ‘The Whalsay Pattern’. Perhaps she was familiar with Maggie and Babbie Jean’s pullovers, living in the same island community at the same time. Emma’s graph shows the four arrows all pointing to the smaller variegated diamond medallion, as the traditional Selbu pattern is. This is the same version as the two jumpers worn by the two friends.

The Lerwick connection

Dating from 1933 is another version of this pattern in a photograph of Kathleen Scott of Lerwick wearing a pullover. Her jumper is chic and modern-looking, close-fitting with cap sleeves and probably knit in cotton or rayon. It is knit in two colours, like the original Selbu version. But unlike the Norwegian or Whalsay versions, the arrows all point downward – two pointing toward the diamond medallion, and two pointing away from it.

Kathleen’s pullover also includes a secondary pattern above the basque and at the cap sleeves. This narrow wavy pattern is also recorded in traditional Selbu knitting, but is unusual in Shetland design.

The Scalloway connection

On the last day of November 1954, Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill celebrated his 80th birthday. In his long and distinguished career, he had served as Home Secretary, First Lord of the Admiralty, Chancellor of the Exchequer, leader of the opposition and twice as Prime Minister. The year before he had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature but also suffered a serious stroke. His momentous birthday was marked by the State Opening of Parliament, where he was presented with gifts from around the world.

One of Churchill’s most ardent fans was Mary Slater (née Goodlad), originally of Burra isle. It was said she had a large portrait of Sir Winston hanging in her Scalloway home. The village itself had been at the centre of the Shetland Bus operations, an important part of the Norwegian resistance movement during World War II. The village still celebrates Norwegian National Day with commemorations for those involved and has strong ties with Norwegian historical and cultural organisations. Most recently the Norwegian Prime Minister opened the new Scalloway Museum and Queen Sonja has visited the village numerous times.

Following a long-standing tradition of sending Shetland knitwear to beloved national figures, Mary knit Sir Winston a sleeveless pullover for his big day. She used a version of the Selbu pattern, in this case not like the pattern found in Whalsay which is the same as the Norwegian, but the same as Kathleen Scott’s of Lerwick, with all arrows pointing downward.

Mary made another change too: she added a fair isle element by changing background and pattern colours to form a narrow horizontal stripe through the centre of the rounded medallion. Only a black and white photo of Sir Winston’s pullover survives but the background appears to be natural white and the pattern is probably moorit. The horizontal stripe is possibly grey and Shetland black. Mary Slater’s husband Robert came from a small island to the west of Scalloway, where his family had sheep. It was common in the first half of the 20th century for knitters who had their own flocks to send fleeces away to Hunter’s of Brora or Pringles, to have the wool spun into yarn, much like mini-mills do today. Neighbours can recall Mary airing hanks from her store of yarn and it is probable that Sir Winston’s slipover was made using wool from the island of Papa.

The other pattern in the jumper is a wavy line just above the ribbing or basque. This is also a Norwegian pattern from Selbu and is not common in Shetland knitwear design. However, it is the same pattern as in Kathleen Scott’s cap sleeves and lower border. It is not known whether Mary knew these patterns originated in Norway or if that choice was deliberate given Churchill’s role in the war. Mary did not call the main pattern ‘Churchill’, although it is now sometimes referred to as such.

The use of Norwegian-inspired patterns increased during and immediately following the war, as resistance fighters and refugees crossed the dangerous waters of the North Sea in fishing boats, wearing their normal, home-made clothing. Shetland knitters saw the patterns on the backs, heads and hands of the Norwegians with increasing frequency and became inspired by them. They enlarged, re-aligned and re-interpreted them but in every case they applied the Shetland stamp by using horizontal bands of colourwork in the background and pattern stitches. These variations change the look of the overall pattern, focusing the eye on one aspect or another. They also allow for endless possibilities for the knitter who wishes to experiment with colour using this lovely Norwegian pattern.

Many thanks to Barbara Johnson, Rosabel Halcrow, Amanda Pottinger and Marina Tait for providing historical information and to Whalsay Heritage Centre for permission to reproduce the wonderful photograph of Babbie Jean and Maggie.

For more information about Selbu patterns, see Anne Bårdsgård, Selbuvotter. Trondheim: Museumsforlaget, 2016.